FT 69. Photo Michel Lechien

The Copts

“It was the Arabs who gave the name Copts (Qibt or Qoubt in Arabic) to the inhabitants of Egypt at the time when Islam arrived” says Marie-Cécile Bruwier, Egyptologist and Scientific Director of the Royal Museum of Mariemont. “At that time, the population comprised indigenous Egyptians and descendants of metropolitan Greeks and Romans.” Most of the autochthons were Christians, but infused by other religions and even paganism.

Over time, many Copts became Muslims. Copts hence designates those who remained Christians, their religious rites and their idioms coming down from ancient Egypt. Today, it is estimated that the Coptic community comprises some 7.5 million people, accounting for almost 10% of the Egyptian population.

Weaving in Egypt

"The textile industry, with its artisanal production, played a leading role in the economic life of ancient Egypt and the quality of its textiles was famous far beyond its frontiers” comments Florence Calament, Curator at the Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum. “Over the centuries, Egyptian weavers never ceased developing their art, giving free rein to their artistic talents through a rich and abundant iconographic vocabulary.”

The Copts used tunics, shawls and curtains as shrouds and this was how archaeologists excavating in Egypt during the 19th and early 20th centuries came to discover great quantities of linen, wool and silk in the Greco-Roman and Byzantine necropolises. Some of these fabrics date from the 2nd century AD. Thanks to the dry climate and the techniques used for burials in Egypt, Coptic fabrics often retained their colours.

FT 50. Photo Michel Lechien

Fragments

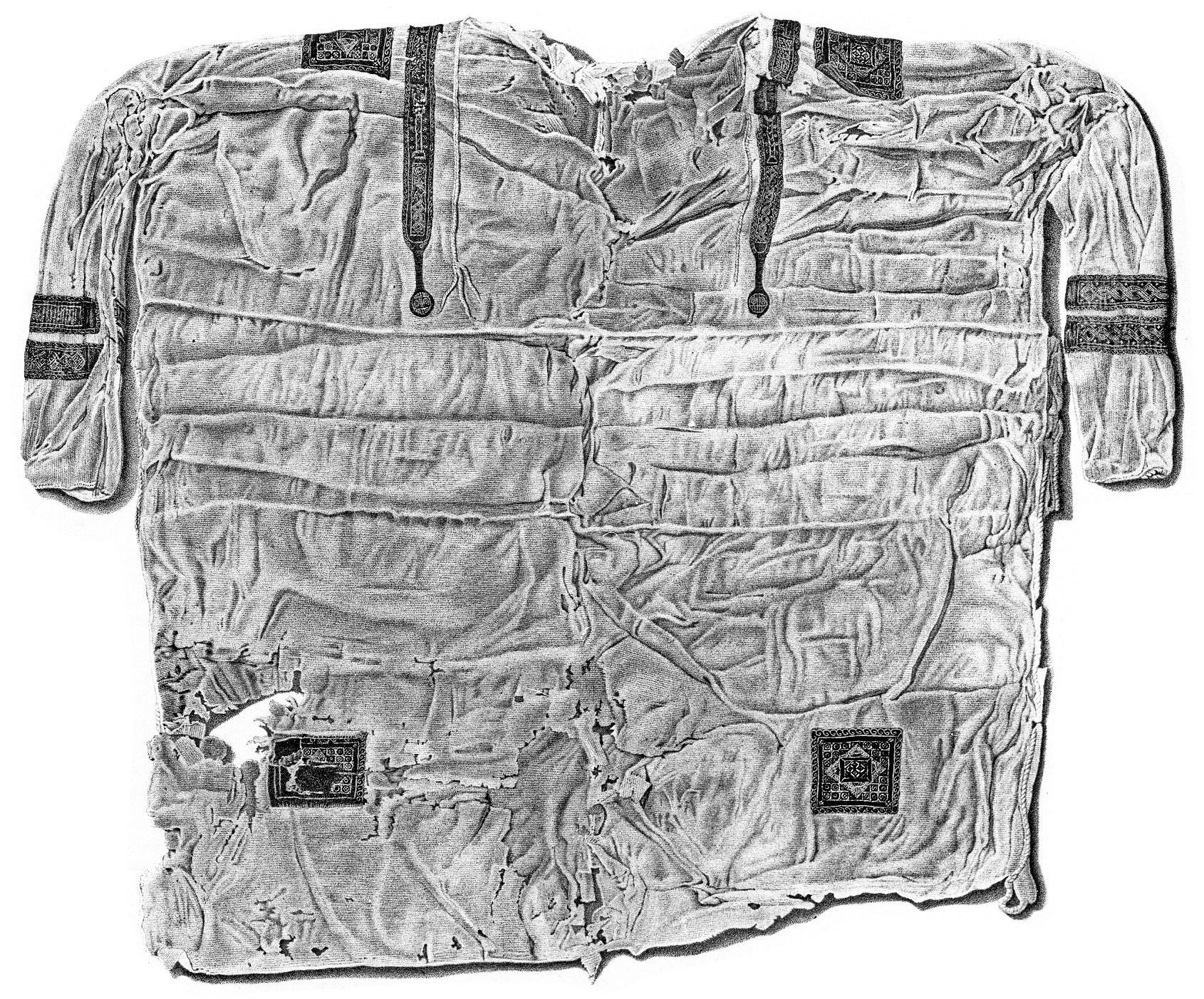

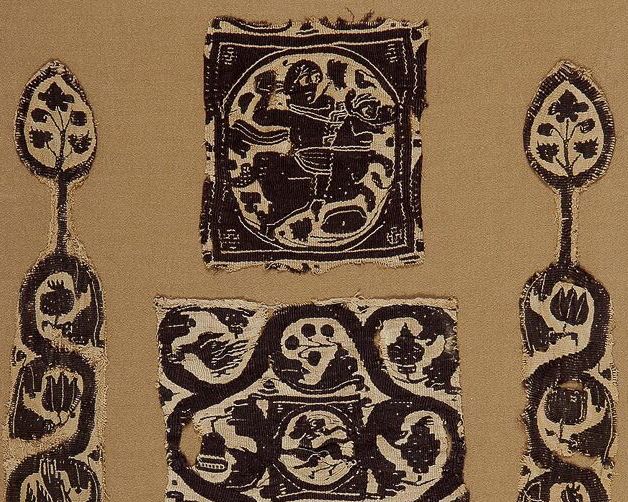

The fragments that remain today are most often tapestries that have been separated from the tunics they decorated. “For purely commercial reasons, the motifs woven into important textiles were frequently cut out and sold separately” explains Chris Verhecken-Lammens, a specialist in textile analysis. “It is therefore not rare to find fragments of a particular piece of clothing or furnishing fabric in different collections.”

These decorative elements were placed at shoulder level and on the lower part of tunics, but also at the neck and the ends of the sleeves. There were square elements known as tabulae and discs called orbiculi. There were also neck trimmings and long or short bands called clavi. Such decoration abounds with details, a characteristic that is specific to Egyptian art of this period.

Coptomania

At the Exposition Universelle de Paris in 1900, French archaeologist Albert Gayet presented the results of excavations he had carried out in the winter of 1898-1899. Around one hundred examples of Coptic textiles and fragments were exhibited in the costume pavilion, a building of over 3,000m₂ that had been erected on the Champs-de-Mars. The pieces were those discovered in the necropolises of Antinopolis, Deir al-Dyk and Dronkah in Middle Egypt, as well as Damietta in the Nile Delta.

Their aesthetic provoked a real craze or “Coptomania”, influencing artists such as Auguste Rodin and Henri Matisse in particular but also fashion designers and others.